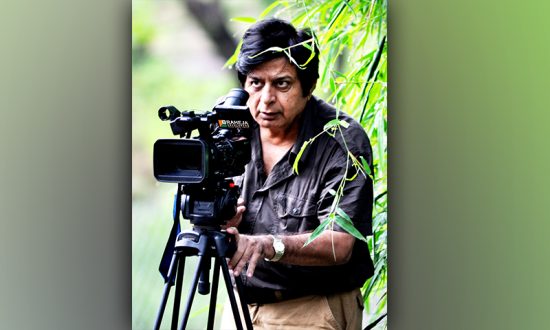

A former member of Project Tiger’s steering committee, under the Ministry of Environment and Forests, Navin M Raheja worked persistently to ensure that the threatened big cat survives in India. He has also been the Chairman of Wildlife Conservation Society. One with the holistic vision, Raheja believes that the development and protection of the environment can happen simultaneously. As a Wildlife enthusiast and photographer, Navin M Raheja says, “Wildlife and Bio-diversity must be preserved. In this corona pandemic, it is high time that we should give importance to environmental sustainability where Wildlife and Bio-diversity will play a vital role.”

There was a time when the Terai zone of sub-Himalayan region, teeming with wildlife and bio-diversity of the finest kind, extended from Jammu to Assam. Tigers, elephants, and even rhinos called it their home. But not anymore. I am afraid if its degradation continues, the Terai as we have known it would pass on into the realm of fantasy land.

This enchanting area was not only the perfect place for flora and fauna to flourish but housed several architectural marvels too. And lest we forget, `Sultana Daku’, India’s own Robin Hood whose fame grew far and wide and who gave sleepless nights to the British rulers, also operated in this region.

For close to 45 years now, being a wildlife enthusiast, film-maker and an active campaigner for a better environment, I have seen the gradual but definite decimation of the Terai area. I have seen how some of the finest wildlife corridors, which gave unrestricted and free access to animals to move from one place to another, have been destroyed, blocked or made totally unfit for the purpose for which they existed. My eyes have seen it all.

But being an optimist at heart, I believe that although we may have reached quite near the point of no return, we have refrained ourselves from crossing the “Lakshman Rekha”. So a ray of hope does exist. Of course, it would be crucial to first understand the nature of the malady before looking for a cure.

Let’s focus on the big picture since doing so would be crucial for the correct diagnosis of the ailment. Till about 70 years ago, the Terai region of present-day Uttarakhand (and even parts of adjoining Uttar Pradesh) was bestowed with one of the best and biggest forest blocks in India. Sprawling grasslands, unending stretches of magnificent Sal forests, numerous water bodies and rich bird and animal life were the chief characteristics of this unique zone. To illustrate a point, wild elephants and other wildlife would regularly migrate between it’s two extreme points: that is, from Haldwani forest division in the Kumaon region of Uttarakhand to the Indo-Gangetic plains which started at Haridwar and stretched right up to Saharanpur.

And then came the human interference to control the affairs of this natural wonder, with both stupendous and horrendous results. The first step was taken in 1936 by officially designating the boundaries of Hailey National Park in the Nainital and Pauri-Garhwal district; after Independence, it was renamed Corbett National Park, to honour renowned hunter-turned-conservationist Jim Corbett. The forest track next to it, consisting of three wildlife sanctuaries (Motichur, Chilla and Rajaji) and extending from Kotdwar to Haridwar till Saharanpur boundary, was first notified as Rajaji National Park in 1983, and subsequently declared Rajaji Tiger Reserve in 2015.

But just as a map is not the territory, not all good intentions lead to desired results. For many years, the wildlife corridor between Corbett and Rajaji Parks, the biggest of its kind in the entire Terai region, remained in perfect health. Elephants, tigers and all other wild animals- bless them, they don’t understand or respect man-made boundaries!- would regularly move from its one corner to another.

Earlier, and I am talking about a period till about decade and a half ago, one could get a sense of this exquisite wildlife corridor while driving from Kalagarh to Kotdwar.

This corridor, whose grasslands would be teeming with wildlife of all kind, extended for about five kilometres from the present urban boundary of Kotdwar towards the stretch going to Kotdwar. The Kandi Road and Khoh river pass through the corridor.

This Corbett-Rajaji corridor gave unfettered access to wildlife to move from one zone to another. On numerous occasions, I used to see big herds of elephants, deer, and even solitary tigers and leopards use the corridor.

How rich was the wildlife which, at one point of time till about six decades ago, would either pass through or live around this corridor? There is verifiable evidence- even today- which exists in the shape of two Forest Rest Houses which the erstwhile British rulers built in this region. These rest houses are at Saneh and Jaffrabad. And both of these, as used to be the British policy at the time, was used for “game hunting”.

Hunting, of course, is now illegal in India but even “game viewing” cannot be experienced in the region. Reflecting the shocking state of affairs (and also, perhaps, our changing sensibilities and priorities), the corridor is now shrunk to mere 300 yards! Nowadays, thanks to the unchecked human encroachment along the length and breadth of the corridor, hardly any animal use it. This is the current state of affairs. An indication of the extreme severity of the situation can be gauged from the recent elephant census reports of Uttarakhand. The official data shows that from 2012 to 2019, the number of elephants in Rajaji Tiger Reserve- who are now virtually cut-off from the adjoining Tiger Reserve due to the “closure” of the corridor- has remained constant at around 300. A recipe for certain doom this is- if nothing else, the genetical health of Rajaji’s elephants will be the first casualty in the present state of affairs.

The vital wildlife corridor between Rajaji and Corbett Reserves did not get obliterated overnight. No sir, great efforts were made by us humans in this direction, with varying doses of human encroachments on forest land, clearing of woods for agriculture and industries, unplanned tourism and boom in human population thrown in for good measure.

This encroachment, which began almost 60 years ago, succeeded in killing the wildlife corridor between Rajaji and Corbett Reserves.

According to some disturbing reports which have started trickling in, the district administration of this region has recommended “regularisation” of the unauthorised human settlements on the forest land. The official communication in this regard has already reached the Uttarakhand Government in Dehradun.

Roughly 100 years ago, the Terai region of Uttarakhand and Uttar Pradesh reverberated with the exploits and stories of `Sultana Daku’, that swashbuckling prince of the brigands. With his “headquarters’’ at several places such as Bijnor, Nijibabad and Gadappu (near Kaladhungi), Sultana became a huge headache for the British rulers.

The Britishers dispatched several armed parties to nab Sultana and his men, but they would all return empty-handed. Much like the present-day Veerappan of South India- who was accounted for about two decades ago- Sultana too enjoyed mass support of the local population and therefore, always managed to give the slip to the British soldiers.

Finally, it dawned on the British Government that a well-planned, concerted effort would be required to nab Sultana. As a first step, Jim Corbett- who knew the terrain quite well- was roped in, followed by two British officers Percy Wyndham and Captain Freddy Young.

The three, aided by 300-plus police force and making it one of the most elaborate manhunts of its time, started spreading the dragnet around Sultana Daku. This here is an extremely rare photograph, of Jim Corbett, Captain Young and Wyndham enjoying a meticulously laid-out lunch during their efforts to arrest Sultana.

Sometime around 1922- there are different versions about the exact date- Sultana Daku was finally nabbed. In June or July 1924, he, along with his 15 associates, was hanged to death.

The Terai area holds many such colourful tales. At the same time, it’s also a vital link between the past, present and future, of its glorious days which have become history and the need to pick up the pieces and recreate its glory once more.

All is still not lost. Uttarakhand has a history of taking pro-wildlife steps in the past. The vast grasslands of the Chilla region of Rajaji Park were, till about two decades ago, occupied by hundreds of `Van Gujjar’ families, who stayed here in their `deras’ (makeshift homes) with thousands of cattle. But intervention by the state authorities led to their rehabilitation in the Pathri and Gaindikhata regions outside the boundary of Rajaji. Today, the once-neglected grasslands of Chila have returned to their pristine glory, and the wildlife (including tigers) have made a remarkable comeback here. Similarly, in the Corbett Tiger Reserve, four villages- Dhela, Jhirna, Kathirao and Laldhang- were relocated outside the protected areas with spectacular results.

The wildlife corridor between Rajaji and Corbett Reserves also deserves a second lease of life. The point of no return is still a few steps away. If nothing else, the raging Coronavirus has taught us the value and sacredness of “all life”. Wildlife doesn’t have a vote, but should that be held against it? Please visualise how Earth would look without humans…Or how a forest would look without birds and animals, its rightful inhabitants? Surely, they deserve a better deal.